Paul Sample (United States, 1896-1974), Matthew VI: 19 (The Auction), 1939, Oil on canvas, 29.5 x 35.5 in. (74.9 x 90.2 cm), Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Myron Hokin, 57.062.000

“Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust consume and where thieves break in and steal; but store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust consumes and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.”

— Holy Bible, Book of Matthew 6:19-21 (New Revised Standard Version)

The title of Matthew VI: 19 (The Auction) (1939) and the Biblical quote it references provide a lens for interpreting American Regionalist artist Paul Sample’s composition. Although Sample emphasized Matthew 6:19 and its warning against collecting treasures on earth, verses 20 and 21 complete the moral message.

Many visual elements complement this Biblical quote. Snow on the ground, barren trees, and a looming sky of greys and mauve serve as metaphors for death. Framed by branches is an apparition of indeterminate gender in bed with a dog, painted lightly, as if faded from memory. The figure gazes upon the scene below as a lifetime’s worth of possessions are auctioned off. Underscoring this ghostly theme, a church and its cemetery are near the horizon. In the foreground, men and women claim their newfound treasures. The scene references the memento mori (Latin: literally, “remember you must die”) adage that “you can’t take it with you,” but Sample also emphasized life with the playful dog and snow-white horse while cues direct the viewer’s gaze toward the baby at the center of the scene. This relationship between life, death, and earthly possessions is the composition’s central theme.

This painting is an important example of Sample’s Regionalist work after he returned to Norwich, Vermont, in 1938 to become artist-in-residence at his alma mater Dartmouth College. He had spent the previous twelve years establishing his artistic career in Los Angeles. It was during this time that Sample and his friend Millard Sheets were named “the best of the west” in a TIME magazine article that debuted Regionalist artists to the nation. Sample’s paintings and watercolors cast him as a chameleon; his artistic style often shifted between those of Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1525-69), Grant Wood (1891-1942), Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975), Alexandre Hogue (1898-1984), Charles Sheeler (1883-1965), and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974).

The Lowe played an important role in promoting the work of Paul Sample after its acquisition of this painting in 1957. In 1984, it mounted a major retrospective, Paul Sample: Ivy League Regionalist, and this painting was on the front cover of the corresponding catalogue.

—Dr. Christina Larson, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Academic Engagement, University of Miami Libraries and Lowe Art Museum. Dr. Larson completed her dissertation, “America Seen through the Work of Paul Sample,” at Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, Ohio) in 2015.

Washington Allston (United States, 1779 – 1843), Jason Returning to Demand His Father's Kingdom, 1807-1808, Oil and chalk on canvas, 426.7 x 609.6 cm. (168 x 240 in.), Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Gift of The Washington Allston Trust, 56.140.000

This mural-sized, unfinished painting by Washington Allston (1779-1843) is one of the largest two-dimensional works in the Lowe Art Museum’s permanent collection. After Allston graduated from Harvard, he went to Rome for additional artistic training. Painted while he was in the Eternal City, this neoclassical composition and the myth it represents complement the Greco-Roman antiquities in the Lowe’s Sylvia and Ray Marchman, Jr. Gallery. Allston composed this work in Rome around 1807, but left Italy in 1808 and boxed the large-scale canvas for shipment to a friend who was living in London. After he returned to the United States, Allston was no longer working in the Neoclassical style but instead shifted his stylistic focus toward Romanticism. Thus, he never attempted to finish the painting. In 1844, (one year after Allston’s death) the artist’s London friend gave the painting to administrators of the Allston estate, which donated it to the Lowe Art Museum in 1956.

While the scale of the Lowe’s canvas is impressive, its composition as an unfinished painting is instructive. Organized geometrically around the statue in the middle ground, the painting features orthogonal lines that direct one’s gaze from the corners in the foreground to the Classical building in the background. Allston’s work includes a terracotta-colored underpainting and figures at various stages of completion with entirely blank areas surrounded by finished design. The artist first made line drawings of the entire scene and modeled (with light and shadow) buildings and a handful of figures in the scene. Allston allowed pigments to dry for months with the intention of later applying the softening, luminous glaze of transparent color. In this painting, he abandoned the work before applying glazes, so only the “dead coloring” remains. By studying this unfinished painting, the viewer can experience and understand Washington Allston’s working process.

Allston’s composition illustrates the ancient Greek myth of “Jason and the Golden Fleece,” one of the oldest examples of a hero’s quest. The story begins when Jason’s uncle Pelias kills his own brother Aeson, King of Iolcos in Thessaly (Jason’s father) to claim the throne. Jason’s mother hides him at the Mountain of Pelion and he returns years later at twenty years old. Jason demands his rightful throne, but his uncle Pelias avoids Jason’s claim by sending him on journeys to kill monsters and retrieve the golden fleece from Southwest Asia. Jason accepted, triumphed, and returned a hero. Allston’s canvas and title (Jason Returning to Demand His Father’s Kingdom) describe the pinnacle of the story when Jason returns to Iolcos and confronts his uncle Pelias after acquiring the golden fleece.

Allston completed a smaller monochromatic drawing (on loan to the Fogg Museum at Harvard University) in preparation for the Lowe’s large canvas. This work offers answers for imagining how the mural-sized painting would have looked if finished, including Jason in the left of center, draped with his golden fleece, surrounded by supporters, and demanding his rightful kingship from his uncle Pelias, standing at the center. The components of this comparative study are like puzzle pieces that complete the flat, unfinished areas of the Lowe’s wall-sized canvas.

— Dr. Christina Larson, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Academic Engagement, University of Miami Libraries and Lowe Art Museum

Washington Allston (United States, 1779 – 1843), Study for Jason Returning to Demand His Father's Kingdom, ca. 1807-1808, Graphite, black and white crayon on paper mounted on canvas, 88.3 x 111.8 cm. (34.75 x 44 in.), Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Loan from The Washington Allston Trust, ©President and Fellows of Harvard College

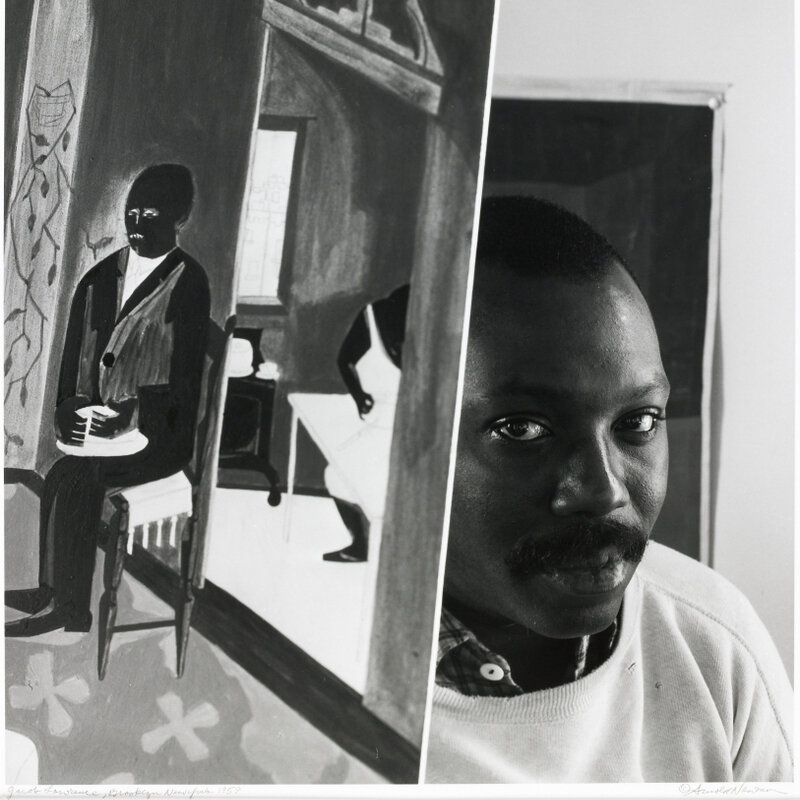

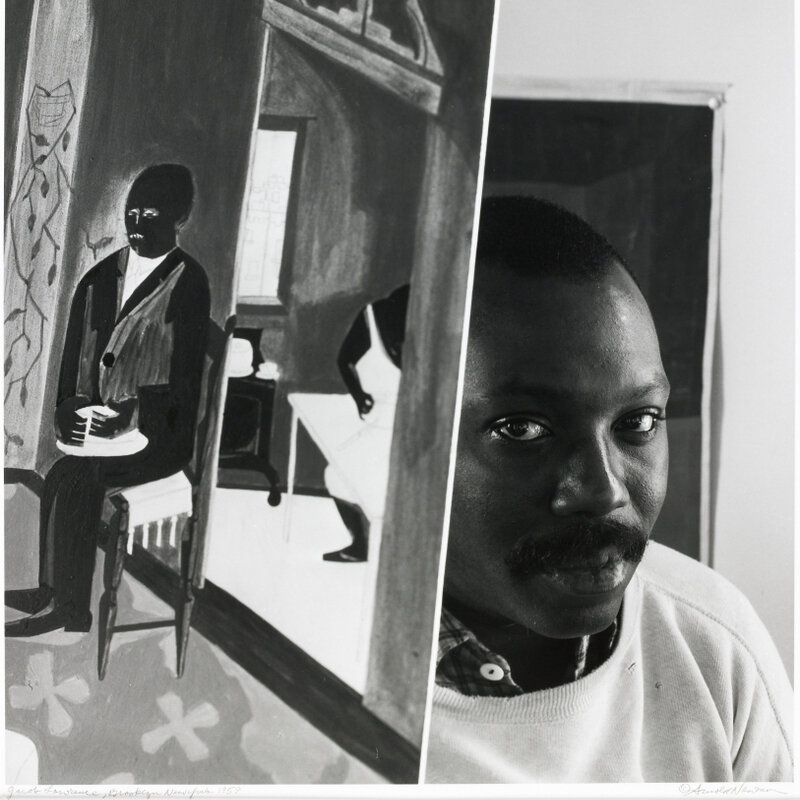

Arnold Newman (United States, 1918-2006) Jacob Lawrence, Brooklyn, New York City, 1959, 1959, Gelatin silver print, 12 ¾ x 10 in. (32.39 x 25.4 cm.) Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Gift of the Estate of the Artist, 2007.31.17, © Arnold Newman Properties/Getty Images

#LoweOnTheGo | Newman Lawrence

“We don’t take pictures with cameras—we take them with our hearts and minds.”

— Arnold Newman

“As late as a few years ago in the 1950’s the Negro had not been included in the general stream of history … Now … there’s a more conscious effort to put the Negro back … in American history … Historians have glossed over the Negro’s part as one of the builders of America … ”

— Jacob Lawrence

This photograph connects two of the most significant American artists of the twentieth century: the photographer Arnold Newman (1918-2006) and the painter Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000). These two men were born around the same year and lived similar life spans. Newman is best known as a portrait photographer of prominent figures and spent his formative years in the Miami area with his family. Compositions like this one, which contributed to Newman’s designation as the “pioneer of the environmental portrait,” are carefully staged to reveal the subject’s personality and spirit in their typical environment.

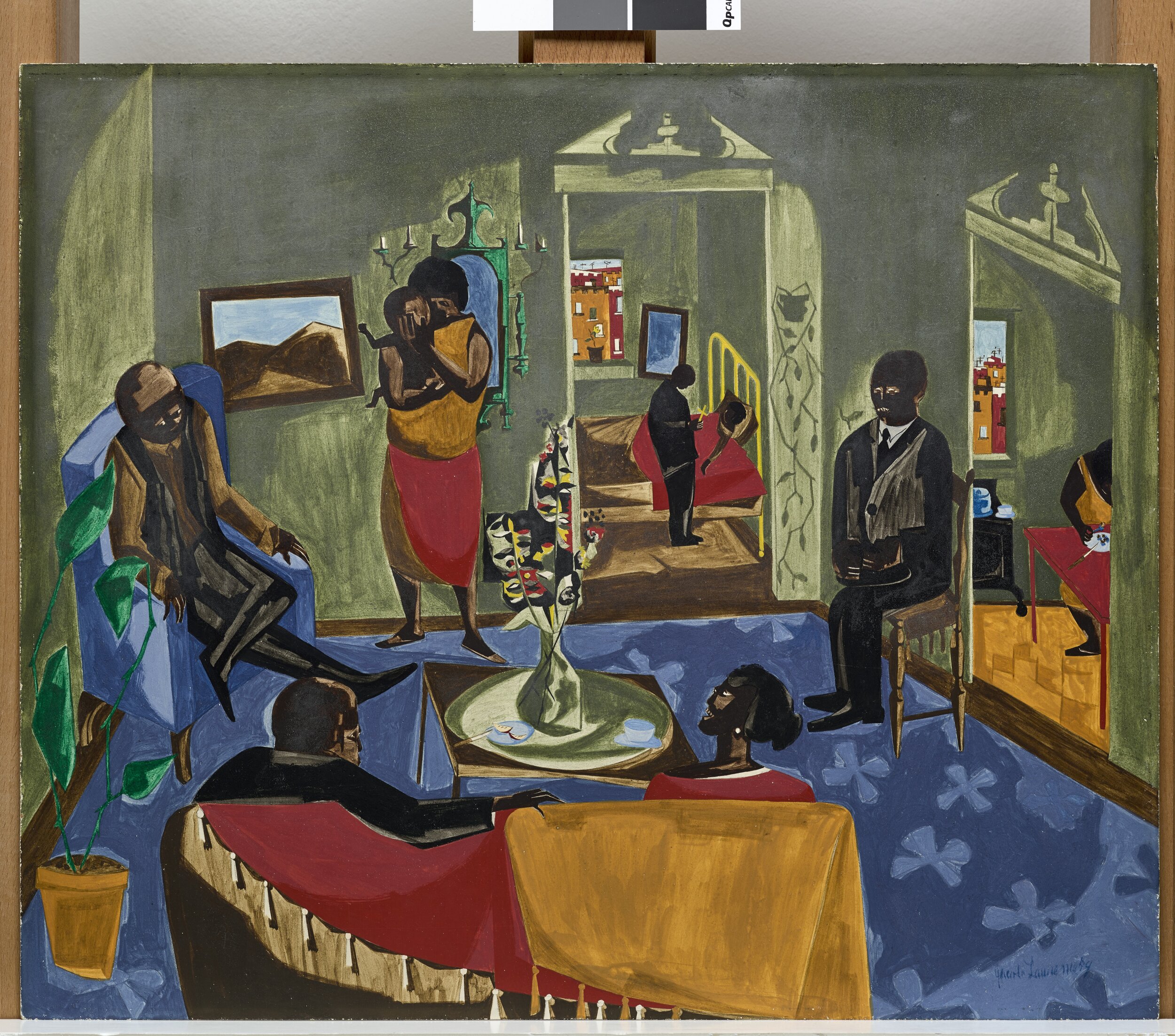

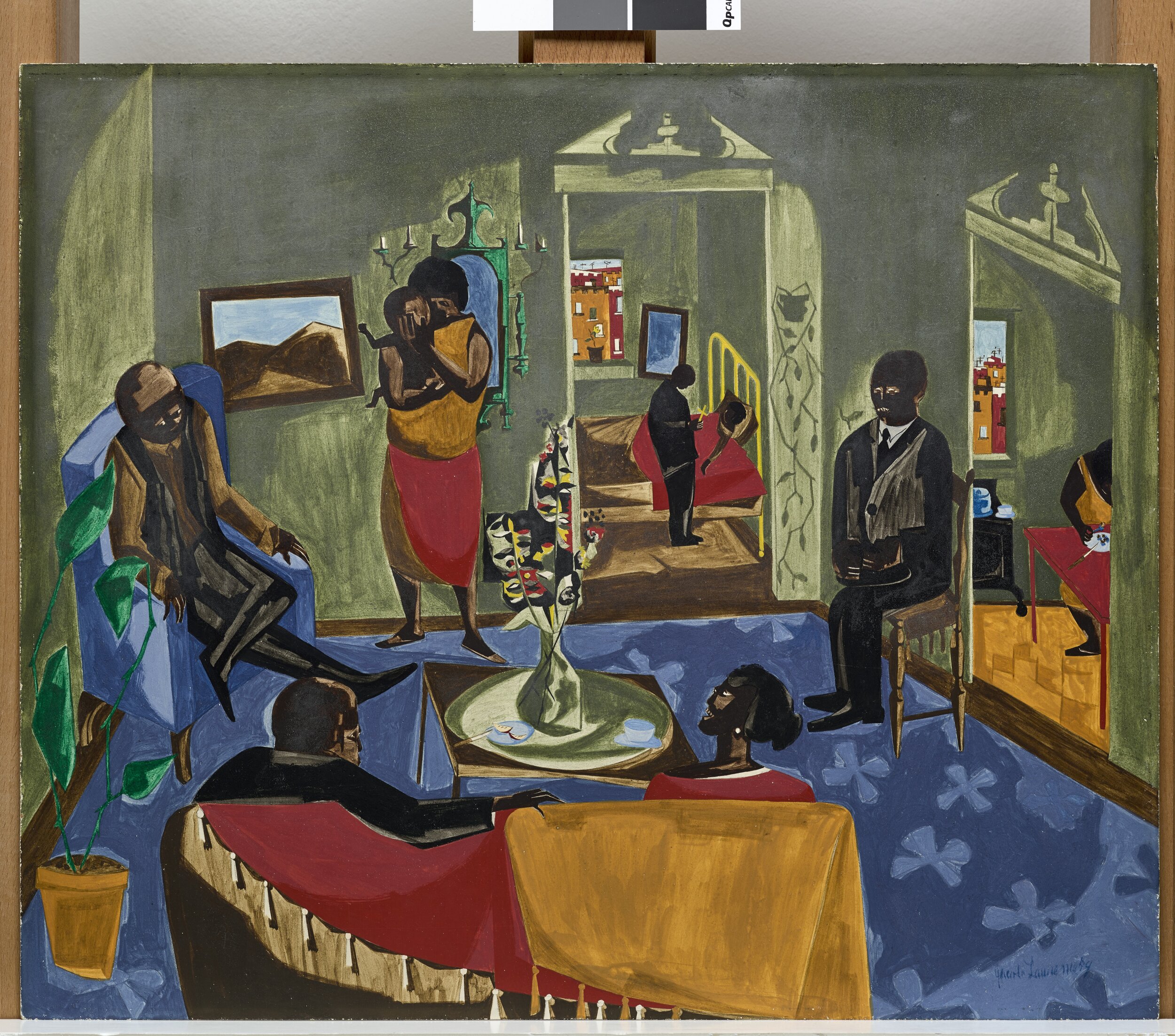

As the sitter for this portrait, Jacob Lawrence is shown with his 1959 painting The Visitors (Dallas Museum of Art), which he painted the same year as this photograph was taken by Newman. Lawrence’s proximity to the painting in the photograph underscores his role as the creator of this work. Just beyond the open doorway in the scene, a minister confers final blessings on a bedridden person. Other family and friends of the community gather, waiting to pay their respects. These African American figures are assembled in a circular pattern, suggesting the cycle of life that begins with the infant held by a woman and ends with the person about to die.

This type of narrative and rich storytelling are hallmarks of paintings and prints by Lawrence. Having grown up in the Harlem neighborhood of New York, Lawrence knew many of the artists, writers, playwrights, photographers, poets, and musicians of the Harlem Renaissance who sought to celebrate African American history and culture while combating racial stereotypes. Lawrence organized his paintings and later prints (starting in 1963) as series, in which individual works function like still frames, collectively telling stories about African American experiences and histories. Newman took this photograph of Lawrence in 1959, only four years after NAACP activist Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat for a white man in Montgomery, Alabama. Throughout his career (which coincided with the American civil rights movement of the 1950s and '60s), Lawrence employed his artwork to promote greater racial equity. His work laid a foundation for younger African American artists who use their visual art to promote visibility and justice for those who have been marginalized.

Likewise, Newman’s work and legacy have influenced countless others. He was born in New York City, grew up in Atlantic City, and later moved to Miami Beach. From 1936 until 1938, he studied painting and drawing at the University of Miami. With these close ties, the Lowe Art Museum began hosting The Arnold and Augusta Newman Endowed Lecture Series in Photography, featuring distinguished photographers who have given public presentations and engaged directly with University of Miami students. In 2020, this program received a $500,000 endowed gift from the Arnold and Augusta Newman Foundation, securing the future of this biannual lecture series while honoring the legacy of the late Arnold Newman.

— Dr. Christina Larson, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Academic Engagement, University of Miami Libraries and Lowe Art Museum.

Jacob Lawrence (United States, 1917-2000), The Visitors, 1959, Tempera on gessoed pane, 27 1/4 × 31 × 1 in. (69.22 × 78.74 × 2.54 cm), Dallas Museum of Art, General Acquisitions Fund, 1984.174, © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Walt Kuhn (United States, 1877-1949), Waiting for the Robert E. Lee, 1934, oil on canvas, 48 1/8 x 44 1/4,” collection of the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Museum purchase through funds from the Friends of Art and Howard and Barbara Garfinkle, 73.999.998

It's simply great, mate, waiting on the levy

Waiting for the Robert E. Lee!

The whistles are blowing, the smokestacks are showing

The ropes they are throwing, excuse me I'm going

To the place where all is harmonious

Even the preacher, he is the dancing teacher!

“Waiting for the Robert E. Lee,” 1912, music by Lewis F. Muir and lyrics by L. Wolfe Gilbert.

Walt Kuhn’s title for this painting refers to the two women performers who seemingly gaze from behind the scenes at the stage. It also alludes to the popular ragtime tune, “Waiting for the Robert E. Lee,” about a steamboat of that name that was performed by Al Jolson (1886-1950) for The Jazz Singer, 1927, and later by Judy Garland (1922-1969), Dean Martin (1917-1995), Neil Diamond (b. 1941), and others. In the early twentieth century, vaudeville performances and musical reviews often featured the song.

The style and subject matter of this composition are typical of Kuhn’s work. Performers dressed in vibrant costumes with their silhouettes outlined in black are representative of the artist’s paintings from this period. Kuhn knew and admired the work of Ashcan School artist Robert Henri (1865-1929), who composed similar paintings of performers with vivid colors. Henri and his followers (including Kuhn) represented the marginalized, lower-class members of society—a tendency that developed from their former roles as newspaper illustrators.

Paintings of performers were common during the Great Depression, and Kuhn was in good company with other American artists of the 1930s who depicted circus imagery, such as Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975), John Steuart Curry (1897-1946), and Paul Sample (1896-1974). Yet Kuhn had an advantage over his contemporaries; his experience directing, designing, and performing in theatre gave him insight into the inner workings of these productions. He also traveled with the circus and devoted much of his career to creating paintings of clowns and circus performers. In addition to portraying other entertainers, Kuhn produced his self-portrait Portrait of the Artist as a Clown (Kansas), 1932 (Collection of Barney A. Ebsworth).

Kuhn’s painting in the Lowe’s collection offers an interesting vantage point into its historical context. Over twenty percent of the population was unemployed at this point in the Great Depression, and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945) had just introduced his New Deal in 1933, which included financial support for visual artists. The circus and vaudeville allowed Americans to escape their realities through entertainment. Contrary to other artists who depicted performers at work, Kuhn instead represented them anticipating their public debut. By showing these women off-stage, the artist spotlighted their humanity rather than their role as performers.

In addition to his contributions as an artist, Walt Kuhn played a major role in the development and promotion of the first Armory Show in New York in 1913. Kuhn worked with fellow Ashcan School artist Arthur B. Davies (1862-1928) to organize this major exhibition of artwork from Europe and the United States. While American artists believed their work was modern in subject matter, they encountered European art that was more stylistically advanced, such as Nude Descending a Staircase (1912) by Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968). With the dynamic display of European and American art, the Armory Show of 1913 had an incredible impact on the direction of American art in the twentieth century.

—Dr. Christina Larson, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Academic Engagement, University of Miami Libraries and Lowe Art Museum.

Irene Rice Pereira (United States, 1902-1971), Man and Machine #1, 1936, Oil on canvas, 35 1/4 x 47 3/8 in. (89.5 x 120.3 cm), Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Gift of John V. Christie, 78.005.007

"Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” is the title of an article written by art historian Linda Nochlin (1931-2017) and published in the January 1971 edition of ARTnews. The writer’s main argument in the piece, which was later republished as part of a full-length text bearing the same title, was that throughout history, women had been denied opportunities that were instead given to men, be they in training, professional recognition, or monetary success. It was not the women who had failed, then, but systems and institutions that had failed them. Nochlin’s piece profoundly influenced feminist art history and coincidentally debuted the same year as the death of the artist Irene Rice Pereira (known as I. Rice Pereira). Throughout her career, the artist signed her work “I. Rice Pereira” to disguise her biological sex, which caused some to mistakenly refer to her as a male artist. Similar to women artists who came before her, Pereira navigated the art world and became a prominent artist in her own time, only to be mostly forgotten by the same institutions that collected her work.

Despite the obstacles she encountered as a woman in a field dominated by men, Pereira achieved great success, evidenced by her numerous exhibitions and inclusion in museum collections. For instance, in 1943, Pereira’s work was part of the show, Exhibition by 31 Women, at Art of This Century, a museum-gallery founded by Peggy Guggenheim (1898-1979). In 1953, Pereira became one of the first women to be featured in a major retrospective with Loren MacIver (1909-98) at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. How did Pereira establish herself as an artist? Beginning in 1927, she trained at the Art Students League, where she attended night classes and developed a strong professional network. In 1935, Pereira helped found and began teaching at the Design Laboratory of New York. Funded by the WPA (Works Progress Administration), the Design Laboratory was an industrial design school with a curriculum that paralleled that of the Bauhaus. As such, it emphasized technology, science, and new materials.

While Pereira is most often recognized as an abstract artist, her early work included figural compositions, portraiture, nautical representations, and cityscapes from her travels in Europe. Pereira’s painting Man and Machine #1 (1936) exemplifies a transition from her previous naturalistic scenes to abstract painting. Three determined, muscular men are entwined with modern machines comprised of belts, pulleys, and levers; one of them (the man in the lower right-hand corner) handles a large bomb with a long, winding fuse that suggests self-destruction. Earlier scholars have associated this painting with the mechanomorphic Cubism of Fernand Léger (1881-1955), but the painting is also in tune with other subjects rendered by Pereira during her early career: depictions of male figures, nautical objects, urban spaces, and machinery. Additionally, Pereira’s painting aligns with other New Deal-era artists and muralists who strategically depicted laboring, muscular men to counter the reality of the weakened nation in which nearly twenty-five percent of the population was unemployed.

The painting Ascending Scale (1937), on the other hand, marks Pereira’s notable shift toward fully abstract compositions. Stemming from her work at the Design Laboratory, Pereira became interested in science, chemistry, space, time, optics, mathematics, physics, and light—so much that, by the 1940s, she began painting directly on glass. As a prominent member of the American Abstract Artists, and with her continued fascination with Bauhaus design and philosophy, Pereira spent her later career creating nonobjective compositions. Ascending Scale is one of the earliest examples of her abstract paintings composed of intersecting, colorful planes with biomorphic forms and geometric shapes outlined in white.

The Lowe has the most comprehensive museum collection in the United States of work by I. Rice Pereira with fifty-two paintings and drawings given to the Museum by collectors William E. Lange, Mr. and Mrs. M. Lubin, Lawrence Rodgers, and John V. Christie. In 1994, the Lowe organized a retrospective of Pereira’s work, Embarking on an Eastward Journey: Irene Rice Pereira’s Early Work, which was curated by Karen A. Bearor and featured a companion catalogue that revisited the work of this great American artist.

—Dr. Christina Larson, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Academic Engagement, University of Miami Libraries and Lowe Art Museum.

Irene Rice Pereira (United States, 1902-71), Ascending Scale, 1937, Oil on canvas, 26 1/2 x 21 3/8 in., Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Gift of John V. Christie, 78.005.001

Nan Goldin (United States, b. 1953), Suzanne and Philippe on the Train, Long Island, 1985 (printed 1997), Cibachrome color print, 13 x 19 1/4 in. (33 x 48.9 cm.), Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Museum Purchase, 78.005.007

“The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1979-86) is the diary I let people read … The diary is my form of control over my life. It allows me to obsessively record every detail. It enables me to remember.” – Nan Goldin

Called the pioneer of diaristic photography, Nan Goldin uses still images of companions and acquaintances to create autobiographical visual narratives. Her work is not that of an outsider documenting others from afar but is instead deeply intimate, personal, and about human connections. Many of her photographic subjects were close friends, roommates, or individuals who went with her to New York nightclubs and parties.

Suzanne and Philippe on the Train, Long Island (1985) features two people whom Goldin represented in at least one other photograph. It is typical in its expression of the intimacy between the subjects and Goldin as the photographer. Philippe rests in Suzanne’s lap as she wraps her arms around his body in a public embrace on a train and gazes directly at Goldin. The snapshot-like quality of this composition is also characteristic of the artist’s work, as she used flash photography at night in public rather than traditional lighting in a private studio setting.

From 1979 until 1986, Goldin photographed friends, lovers, drag queens, transexual people, those with drug addictions, friends living with HIV/AIDS, and others from the underground cultures of New York, Boston, and Berlin. These photographs constitute her most famous series, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a personal narrative created from the artist’s own experiences. This photograph of Suzanne and Philippe is just one of around 700 images she captured to chronicle relationships, power, abuse, drug addiction, identity, autonomy, and sexuality. Like still frames of film, these images were set to music and toured nightclubs during the mid-1980s in the United States and Europe. A selection of 127 photographs from the series was published as a book of the same name in 1986. More recently (2016), New York’s Museum of Modern Art exhibited these 700 photographs in the exhibition Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, which set the images to music; an homage to their initial multisensory nightclub displays.

— Dr. Christina Larson, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Academic Engagement, University of Miami Libraries and Lowe Art Museum.

Walker Evans (United States, 1903-75) Brooklyn Bridge, New York City, 1929, Gelatin silver print, Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Gift of an Anonymous Donor, 80.0185.44

“Down Wall, from girder into street noon leaks,

A rip-tooth of the sky’s acetylene;

All afternoon the cloud flown derricks turn …

Thy cables breathe the North Atlantic still.”

– Hart Crane, 1899-1932, excerpt from “To Brooklyn Bridge,” 1930

This stanza by Hart Crane (1899-1932) is from his poem “To Brooklyn Bridge,” produced just one year after Walker Evans (1903-75) took this photograph and eight others in 1929. This homage to architecture, photography, and poetry was later featured in a 1994 portfolio with the printed poem by Crane and nine photogravures of the Brooklyn Bridge by Evans. When Evans captured this image and when Crane penned his poem, the Brooklyn Bridge was still considered a modern marvel and an icon of industrial achievement. Opened to traffic in 1883, it was the largest suspension bridge in the world; its towers scraped the sky—higher than any other structures in the Western Hemisphere at the time.

Photographed in 1929, likely prior to the Stock Market Crash on Black Tuesday of October 29, 1929, this image by Evans is testament to the strength of industry, ingenuity, and modernity of the United States and especially of New York. With Wall Street just a short walk away from this vantage point, though, the image also marks the apex of abrupt change from the Roaring ‘20s to the Great Depression years of the 1930s.

The Brooklyn Bridge image represents a modern aesthetic, emphasizing the Gothic arches of the structure and complex pattern of the bridge’s cables that converge with one-point perspective. Straight photography like this often features geometric patterns and details rather than structures in their entirety. This genre relates to photography by Paul Strand (1890-1976) and paintings by Charles Sheeler (1883-1965) who famously collaborated on the first American avant-garde film Manhatta (1920). Inspired by the poem "Mannahatta" (1860) by Walt Whitman (1819-92), their film presented modern scenes (similar to still photography) of lower Manhattan’s people, cityscapes, and architecture.

As early as 1917, Strand had presented his straight photography in the Camera Work publication overseen by Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), launching a new, modern aesthetic that deviated greatly from earlier Pictorialist compositions with their soft focus and typically natural subject matter. Instead, straight photography centered on industrial aspects of modern life, cropped images, and typically no manipulation in the dark room. In many ways, the Brooklyn Bridge series by Evans in the late 1920s offered another iteration of previous New York cityscapes by Strand and Sheeler.

Evans is most often noted for his work as a Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographer during the Great Depression, and his humanistic scenes from this era are in stark contrast to the industrial views of his Brooklyn Bridge series. His photographs of the Burroughs family in Alabama and other portraits during the 1930s that illustrate James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) became iconic images, documenting the drastic impact of the Great Depression.

— Christina Larson, Ph.D., Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Academic Engagement, University of Miami.

Henry Salem Hubbell (United States, 1870-1949) Gloriana, 1925, Oil on canvas, 53 1/2 x 53 1/2 inches, Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Gift of William Lewin, 57.176.005

“One day, you will be called a great colorist.”

- James Abbott McNeil Whistler (1834-1903) to his student, Henry Salem Hubbell (1870-1949)

In 1924, Henry Salem Hubbell moved to Miami, where he built his self-designed home in Miami Beach that he called “Casa Rosita,” named for his wife and fellow artist Rose Strong Hubbell (1870-1944). Hubbell’s vision for Miami was that it would become a center for art and education. Shortly after moving to Miami, Hubbell painted Gloriana (1925), which is typical of his portraits of young women adorned in fashionable attire seated in lavish interiors. Hubbell was mostly recognized for his portraiture and social genre scenes. This composition is a striking balance of negative and positive space, with a blank, cream wall in the background juxtaposed with the woman who sits upon colorfully patterned furniture.

Hubbell’s road to Miami was winding and varied, where he learned from leading artists of his time and important artists from the past. He was a contemporary of Gari Melchers (1860-1932) and other American Impressionists; like them, he journeyed to Paris.

Originally from Kansas, Hubbell initially studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago starting in 1887 under William Merritt Chase (1849-1916), who taught the next generation of American artists. It was there that Hubbell met fellow art student Nellie Rose Strong, and the couple married in 1895. Three years later in the autumn of 1898, they moved to Paris, where Hubbell Studied at Académie Julian under William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) and Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921). While the earlier French Impressionists had rebelled against Bouguereau and the French academic painters, it is interesting that Hubbell—an American Impressionist—learned from the artist whom the earlier generation had reviled. Hubbell also learned from the Old Masters, such as Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) and Titian (Tiziano Vecelli, 1488/90-1576) whose work he studied in Madrid.

In Winter 1898, Hubbell met American expatriate James Abbott McNeil Whistler (1834-1903), who became one of his greatest mentors at the Académie Carmen (founded by Whistler) when it debuted in Paris that year. Hubbell studied with Whistler as a private pupil for a relatively short time, but with profound impact—especially on Hubbell’s subject matter, loose brushwork, color, and style. The last notable European experience for Hubbell began in 1908 when he joined the American art colony at Giverny, becoming part of the Giverny Circle of American Impressionists. While there, Hubbell became a neighbor and friend of Claude Monet, who was another important influence.

The Hubbells returned to the United States in 1910, initially to Chicago, then to New York, and eventually to Pittsburgh, where he became head of the Painting Department at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). After moving to Miami in 1924, Hubbell painted portraits of leading American figures, including President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945), Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone (1872-1946), and other college presidents, judges, architects, and artists.

Henry Salem Hubbell was Miami’s American Impressionist; please visit the Lowe to see other American Impressionist artists featured in these two exhibitions:

An American Master at Home and Abroad: Gari Melchers (1860-1932) (November 18, 2021 – February 13, 2022)

American Impressionism: Treasures from the Daywood Collection (November 18, 2021 – February 13, 2022)

—Dr. Christina Larson, Assistant Director, University of Miami Center for the Humanities